Jarvis Island

Nickname: Bunker Island | |

|---|---|

NASA satphoto of Jarvis Island; note the submerged reef beyond the eastern end. | |

| Etymology | Edward, Thomas and William Jarvis |

| Geography | |

| Location | South Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 0°22′S 160°0′W / 0.367°S 160.000°W |

| Archipelago | Line Islands |

| Area | 4.5 km2 (1.7 sq mi) |

| Length | 3.26 km (2.026 mi) |

| Width | 2.22 km (1.379 mi) |

| Coastline | 8.54 km (5.307 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 7 m (23 ft) |

| Administration | |

United States | |

| Status | unincorporated |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 0 |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone | |

| Jarvis Island National Wildlife Refuge | |

| |

| Designated | 1974 |

| Website | www |

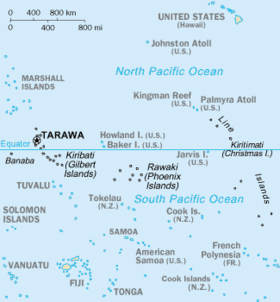

Jarvis Island (/ˈdʒɑːrvɪs/; formerly known as Bunker Island or Bunker's Shoal) is an uninhabited 4.5 km2 (1.7 sq mi) coral island located in the South Pacific Ocean, about halfway between Hawaii and the Cook Islands.[1] It is an unincorporated, unorganized territory of the United States, administered by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service of the United States Department of the Interior as part of the National Wildlife Refuge system.[2] Unlike most coral atolls, the lagoon on Jarvis is wholly dry.

Jarvis is one of the Line Islands and, for statistical purposes, is also grouped as one of the United States Minor Outlying Islands. Jarvis Island is the largest of three U.S. equatorial possessions, which include Baker Island and Howland Island.[3]

The US claimed it in the 19th century and mined it for guano. In the 20th century, it was the subject of a small settlement. It was attacked during WW2 and evacuated, leaving some buildings and a day beacon. In modern times, it is managed as a nature reserve.

Geography and ecology

[edit]

While a few offshore anchorage spots are marked on maps, Jarvis Island has no ports or harbors, and swift currents are a hazard. There is a boat landing area in the middle of the western shoreline near a crumbling day beacon and another near the island's southwest corner.[4] The center of Jarvis island is a dried lagoon where deep guano deposits accumulated, which were mined for about 20 years during the nineteenth century. The island has a tropical desert climate, with high daytime temperatures, constant wind, and intense sun. Nights, however, are quite cool. The ground is mostly sandy and reaches 23 feet (7.0 meters) at its highest point. The low-lying coral island has long been noted as hard to sight from small ships and is surrounded by a narrow fringing reef.

Jarvis Island is one of two United States territories that are in the southern hemisphere (the other is American Samoa). Located only 25 miles (40 km) south of the equator, Jarvis has no known natural freshwater lens and scant rainfall.[5][6] This creates a very bleak, flat landscape without any plants larger than shrubs.[7] There is no evidence that the island has ever supported a self-sustaining human population. Its sparse bunch grass, prostrate vines, and low-growing shrubs are primarily a nesting, roosting, and foraging habitat for seabirds, shorebirds, and marine wildlife.[2]

Jarvis Island was submerged underwater during the latest interglacial period, roughly 125,000 years ago, when sea levels were 5–10 meters (16–33 ft) higher than today. As the sea level declined, the horseshoe-shaped lagoon formed in Jarvis Island's center.[8]

Topographic isolation

[edit]Jarvis Island's highest point has a topographic isolation of 380.57 kilometers (236.48 mi; 205.49 nmi), with Joe's Hill on Kiritimati being the nearest higher neighbor.[9][10]

Time zone

[edit]Jarvis Island is located in the Samoa Time Zone (UTC -11:00), the same time zone as American Samoa, Kingman Reef, Midway Atoll, and Palmyra Atoll.

Birds

[edit]Jarvis Island once held some of the largest seabird breeding colonies in the tropical ocean. Still, guano mining and the introduction of rodents have ruined much of the island's native wildlife. Eight breeding species were recorded in 1982, compared to thirteen in 1996 and fourteen in 2004. The Polynesian storm petrel had made its return after over 40 years of absence from Jarvis Island, and the number of Brown noddies multiplied from just a few birds in 1982 to nearly 10,000. Just twelve Spectacled terns were recorded in 1982, but by 2004, over 200 nests were found there.[11] The island, with its surrounding marine waters, has been recognized as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International because it supports colonies of lesser frigatebirds, brown and masked boobies, red-tailed tropicbirds, Polynesian storm petrels, blue noddies and sooty terns, as well as serving as a migratory stopover for bristle-thighed curlews.[12]

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]Jarvis Island is unlikely to have hosted permanent human occupation before its use for guano mining. However, it is possible the island was utilized as a waypoint or stopover island by Polynesian voyagers. The remoteness of the island and a lack of freshwater resources have prevented large-scale archaeological surveys from taking place.[13]

Discovery

[edit]The island's first known sighting by the British on August 21, 1821, by the British ship Eliza Francis (or Eliza Frances) owned by Edward, Thomas and William Jarvis[14][15] and commanded by Captain Brown. The island was visited by whaling vessels until the 1870s.

The U.S. Exploring Expedition surveyed the island in 1841.[16] In March 1857 the island was claimed for the United States under the Guano Islands Act and formally annexed on February 27, 1858.[17]

Nineteenth-century guano mining

[edit]The American Guano Company, incorporated in 1857, established claims regarding Baker Island and Jarvis Island, recognized under the U.S. Guano Islands Act of 1856.[18][19] Beginning in 1858, several support structures were built on Jarvis Island, along with a two-story, eight-room "superintendent's house" featuring an observation cupola and wide verandahs. Tram tracks were laid down to bring mined guano to the western shore.[20] One of the first loads was taken by Samuel Gardner Wilder.[21] Laborers for the mining operations came from around the Pacific, including from Hawaiʻi; the Hawaiian laborers named Baker Island "Paukeaho", meaning 'out of breath' or 'exhausted', which is indicative of the hard work needed.[22]

For the following 21 years, Jarvis was commercially mined for guano sent to the United States as fertilizer. Still, the island was abruptly abandoned in 1879, leaving behind about a dozen buildings and 8,000 metric tons (8,800 short tons) of mined guano.

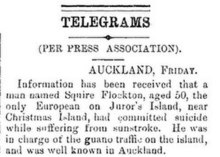

New Zealand entrepreneurs, including photographer Henry Winkelmann, then made unsuccessful attempts to continue guano extraction on Jarvis, and the two-story house was sporadically inhabited during the early 1880s. Squire Flockton was left alone on the island as caretaker for several months and committed suicide there in 1883, apparently from gin-fueled despair.[24] His wooden grave marker was a carved plank which could be seen in the island's tiny four-grave cemetery for decades.[25]

John T. Arundel & Co. resumed mining guano from 1886 to 1899.[26][27] The United Kingdom annexed the island on June 3, 1889. Phosphate and copra entrepreneur John T. Arundel visited the island in 1909 on the maiden voyage of the S.S. Ocean Queen, and near the beach landing on the western shore, members of the crew built a pyramidal day beacon made from slats of wood, which was painted white.[25] The beacon was standing in 1935,[28] and remained until at least 1942.

Wreck of barquentine Amaranth

[edit]

On August 30, 1913, the barquentine Amaranth (C. W. Nielson, captain) was carrying a cargo of coal from Newcastle, New South Wales, to San Francisco when it wrecked on Jarvis' southern shore.[22] Ruins of ten wooden guano-mining buildings, the two-story house among them, could still be seen by the Amaranth crew, who left Jarvis aboard two lifeboats. One reached Pago Pago, American Samoa, and the other made Apia in Samoa. The ship's scattered remains were noted and scavenged for many years, and rounded fragments of coal from the Amaranth's hold were still being found on the south beach in the late 1930s.[29][30]

Millersville (1935–1942)

[edit]

Jarvis Island was reclaimed by the United States government and colonized from March 26, 1935, onwards, under the American Equatorial Islands Colonization Project.[31] President Franklin D. Roosevelt assigned administration of the island to the U.S. Department of the Interior on May 13, 1936.[2] Starting as a cluster of large, open tents pitched next to the still-standing white wooden day beacon, the Millersville settlement on the island's western shore was named after a bureaucrat with the United States Department of Air Commerce. The settlement grew into a group of shacks built mostly with wreckage from the Amaranth (lumber from which was also used by the young Hawaiian colonists to build surfboards), but later, stone and wood dwellings were built and equipped with refrigeration, radio equipment, and a weather station.[32] A crude aircraft landing area was cleared on the island's northeast side, and a T-shaped marker intended to be seen from the air was made from gathered stones, but no airplane is known to have ever landed there. According to the 1940 U.S. Census, Jarvis Island had a population of three people.[33]

At the beginning of World War II, an Imperial Japanese Navy submarine surfaced off the west coast of the island. Believing that a U.S. Navy submarine had come to fetch them, the four young colonists rushed down the steep western beach in front of Millersville towards the shore. The submarine answered their waves with fire from its deck gun, but no one was hurt in the attack. On February 7, 1942, the USCGC Taney evacuated the colonists, then shelled and burned the dwellings. The roughly cleared landing area on the island's northeast end was later shelled by the Japanese, leaving crater holes.[34]

International Geophysical Year

[edit]Jarvis was visited by scientists during the International Geophysical Year from July 1957 until November 1958. In January 1958, all scattered building ruins from the nineteenth-century guano diggings and the 1935–1942 colonization attempt were swept away without a trace by a severe storm that lasted several days and was witnessed by scientists. When the IGY research project ended, the island was abandoned again.[35] By the early 1960s, a few sheds, a century of accumulated trash, the scientists' house from the late 1950s, and a solid, short lighthouse-like day beacon built two decades before were the only signs of human habitation on Jarvis.

National Wildlife Refuge

[edit]

On June 27, 1974, Secretary of the Interior Rogers Morton created Jarvis Island National Wildlife Refuge, which was expanded in 2009 to add submerged lands within 12 nautical miles (22 km) of the island. The refuge now includes 1,273 acres (5.15 km2) of land and 428,580 acres (1,734.4 km2) of water.[36] Along with six other islands, the island was administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as part of the Pacific Remote Islands National Wildlife Refuge Complex. In January 2009, that entity was upgraded to the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument by President George W. Bush.[37]

A feral cat population, descendants of cats likely brought by colonists in 1937,[38] wrought disruption to the island's wildlife and vegetation.[39][40] Including the complete removal of rats, but not the mice,[41] which had been introduced to the island previously.[41] These cats were removed through efforts which began in the mid-1960s and lasted until 1990 when they were completely eradicated.[42] Since cats were removed, seabird numbers and diversity have increased.[43] Among the seabirds that returned to Jarvis Island with gray-backed terns rebuilding quickly and petrels taking longer to reestablish themselves on the island.[41][43]

Nineteenth-century tram track remains can be seen in the dried lagoon bed at the island's center, and the late 1930s-era lighthouse-shaped day beacon still stands on the western shore at the site of Millersville.

Public entry to anyone, including U.S. citizens, on Jarvis Island requires a special-use permit and is generally restricted to scientists and educators. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the United States Coast Guard periodically visit Jarvis.[6]

Transportation

[edit] Jarvis Island Light in 2003 | |

| |

| Location | Jarvis Island, Line Islands, US |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 0°22′14″S 160°00′24″W / 0.37044°S 160.00669°W |

| Tower | |

| Constructed | 1935 |

| Construction | masonry |

| Height | 5 m (16 ft) |

| Shape | circular truncated tower, no lantern[44] |

| Markings | stripe (red, white, horizontal direction) |

| Light | |

| Deactivated | 1942 |

There is no airport on the island, nor does the island contain any large terminal or port. A day beacon near the middle of the west coast is in poor condition and no longer painted. Some offshore anchorage is available.[45]

Military

[edit]As a U.S. territory, the defense of Jarvis Island is the responsibility of the United States. All laws of the United States are applicable on the island.[45]

See also

[edit]- Howland and Baker islands

- List of Guano Island claims

- Under a Jarvis Moon, an 88-minute 2010 documentary

References

[edit]- ^ Darwin, Charles; Bonney, Thomas George (1897). The structure and distribution of coral reefs. New York: D. Appleton and Company. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-520-03282-8.

- ^ a b c "Jarvis Island". DOI Office of Insular Affairs. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2007.

- ^ Rauzon, Mark J. (2016). Isles of Amnesia: The History, Geography, and Restoration of America's Forgotten Pacific Islands. University of Hawai'i Press, Latitude 20. Page 38. ISBN 9780824846794.

- ^ "Jarvis Island". The World Factbook. CIA. 2003. Archived from the original on September 8, 2006. Retrieved January 26, 2007.

- ^ Pacific Remote Islands National Wildlife Refuge Complex, Jarvis Island NWR Draft CCP EA, August 2007, retrieved November 25, 2010: "No information is available on the subsurface hydrology of Jarvis Island. However, its small size and prevailing arid rainfall conditions would not likely result in a drinkable groundwater lens formation. During staff visits to Jarvis, potable water is carried in containers to the island for short visits."

- ^ a b "United States Pacific Island Wildlife Refuges". Retrieved January 26, 2007.

- ^ "Jarvis Island – Pacific Biodiversity Information Forum photographs". Archived from the original on February 11, 2008. Retrieved January 9, 2008.

- ^ Rauzon, Mark J. (2016). Isles of Amnesia: The History, Geography, and Restoration of America's Forgotten Pacific Islands. University of Hawai'i Press, Latitude 20. Page 48. ISBN 9780824846794.

- ^ "Jarvis High Point, U.S. Minor Pacific Islands". Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ "Joes Hill, Kiribati". Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ Rauzon, Mark J. (2016). Isles of Amnesia: The History, Geography, and Restoration of America's Forgotten Pacific Islands. University of Hawai'i Press, Latitude 20. Pages 38 and 56. ISBN 9780824846794.

- ^ "Jarvis Island". BirdLife Data Zone. BirdLife International. 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Jarvis Island National Wildlife Refuge: Comprehensive Conservation Plan (Report). U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. September 24, 2008. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ "North Pacific Pilot page 282". Archived from the original (png) on February 11, 2008. Retrieved January 26, 2007.

- ^ "R. v. Higgins, Fuller, Anderson, Thomas, Belford and Walsh". legal proceeding. Archived from the original on October 15, 2015. Retrieved January 25, 2007.

- ^ Stanton, William (1975). The Great United States Exploring Expedition. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 232. ISBN 978-0520025578.

- ^ Orent, Beatrice; Reinsch, Pauline (1941). "Sovereignty over Islands in the Pacific". American Journal of International Law. 35 (3): 443–461. doi:10.2307/2192452. ISSN 0002-9300. JSTOR 2192452.

- ^ "GAO/OGC-98-5 – U.S. Insular Areas: Application of the U.S. Constitution". U.S. Government Printing Office. November 7, 1997. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ^ "The Guano Companies in Litigation—A Case of Interest to Stockholders". New York Times. May 3, 1865. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ^ O'Donnell, Dan (January 1, 1995). "The nineteenth century Pacific guano trade". The Bulletin of the Australian Institute for Maritime Archaeology. 19 (2): 27–32.

- ^ George F. Nellist, ed. (1925). "Samuel Gardner Wilder". The Story of Hawaii and Its Builders. Honolulu Star Bulletin.

- ^ a b Quan Bautista, Jesi; Smith, Savannah (2018). Early Cultural and Historical Seascape of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument: Archival and Literary Research Report (Report). NOAA Fisheries Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center. p. 3. doi:10.25923/fb5w-jw23.

- ^ Auckland Star, Volume XIX, Issue 3978, 28 April 1883. p. 2.

- ^ Gregory T. Cushman (March 25, 2013). Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World: A Global Ecological History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 98–. ISBN 978-1-107-00413-9.

- ^ a b Arundel, Sydney (1909). "Kodak photographs, Jarvis Island". Steve Higley. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ Ellis, Albert F. (1935). Ocean Island and Nauru; Their Story. Sydney, Australia: Angus and Robertson, limited. OCLC 3444055.

- ^ Maslyn Williams & Barrie Macdonald (1985). The Phosphateers. Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0-522-84302-6.

- ^ Edwin H. Bryan, Jr. (1974). "Panala'au Memoirs". Pacific Scientific Information Center – Bernice P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ Bryan, E.H. "Jarvis Island" Archived May 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: July 7, 2008.

- ^ Tengan, Ty P. Kawika (2004). "Of colonization and Pono in Hawai'i". Peace Review. 16 (2): 157–167. doi:10.1080/1040265042000237699. ISSN 1040-2659.

- ^ McConnell, D. R. (April 29, 2024). "Prospects for Marine Minerals in the US Pacific OCS and EEZ". Paper Presented at the Offshore Technology Conference. OTC. doi:10.4043/35266-MS.

- ^ Bryan, Edwin H., Jr. Panala'au Memoirs. Retrieved: July 7, 2008. Contains several photos of the Millersville settlement and a diary of events in the colony.

- ^ "Sixteenth Census of the United States: Population, Volume I, Number of Inhabitants, Hawaii (Table 4)", United States census, 1940; Washington, D.C.; page 1211,. Retrieved on October 29, 2021.

- ^ "History of Jarvis Island". "World War Two" section of article. Retrieved January 25, 2007. Shell holes were later noted in the aircraft landing area.

- ^ The IGY station chief was Otto H Homung (d. 1958), who apparently died on the island and may have been buried there.

- ^ White, Susan (October 26, 2011). "Welcome to Jarvis Island National Wildlife Refuge". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on September 4, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- ^ Bush, George W. (January 6, 2009). "Establishment of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument: A Proclamation by the President of the United States of America". White House. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- ^ Hess, S. C.; Jacobi, J. D. (2011). "The history of mammal eradications in Hawai'i and the United States associated islands of the Central Pacific". Proceedings of the International Conference on Island Invasives: 67–73.

- ^ Rauzon, Mark J. (1985). "Feral cats on Jarvis Island: their effects and their eradication". Atoll Research Bulletin. 282: 1–30. doi:10.5479/si.00775630.282.1. ISSN 0077-5630.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, Ralph D.; Rauzon, Mark J. (1986). "Foods of Feral Cats Felis catus on Jarvis and Howland Islands, Central Pacific Ocean". Biotropica. 18 (1): 72. Bibcode:1986Biotr..18...72K. doi:10.2307/2388365. JSTOR 2388365.

- ^ a b c Dilley, Ben J.; Schramm, Michael; Ryan, Peter G. (2017). "Modest increases in densities of burrow-nesting petrels following the removal of cats (Felis catus) from Marion Island". Polar Biology. 40 (3): 625–637. Bibcode:2017PoBio..40..625D. doi:10.1007/s00300-016-1985-z. ISSN 0722-4060.

- ^ "Jarvis Island National Wildlife Refuge". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- ^ a b Rauzon, M. J.; Forsell, D. J.; Flint, E. N.; Gove, J. M. (2011). "Howland, Baker and Jarvis Islands 25 years after cat eradication: the recovery of seabirds in a biogeographical context". Island Invasives: Eradication and Management (PDF). p. 346. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 10, 2013. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ Rowlett, Russ. "Lighthouses of U.S. Pacific Remote Islands". The Lighthouse Directory. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ^ a b "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

External links

[edit]- Jarvis Island Home Page Website with photos, weather, and more.

- Jarvis Island information website Has several photos of the old Millersville settlement, together with more modern photos of the island.

- WorldStatesmen Offers brief data on Jarvis Island.

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Jarvis Island National Wildlife Refuge The Jarvis Island refuge site.

- Jarvis Island

- Pacific islands claimed under the Guano Islands Act

- Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument

- Former populated places in Oceania

- Uninhabited Pacific islands of the United States

- Island restoration

- Pacific Ocean atolls of the United States

- United States Minor Outlying Islands

- National Wildlife Refuges in the United States insular areas

- Protected areas established in 1974

- Coral islands

- 1889 establishments in the British Empire

- Important Bird Areas of United States Minor Outlying Islands

- Important Bird Areas of the Line Islands

- Seabird colonies